History

Before the name Mae Hong Son enters recorded history in the 19th century, the region – a deep valley system hemmed by dense mountains, is thought to have been inhabited by a collection of autonomous farming communities of mostly Burmese origin – predominantly the Shan and Karen people.

Prior to the fixing of borders between Burma and Thailand the lands surrounding the Salween river had been heavily contested by leaders of Shan state in Burma on the west bank, and Lan-Na (today’s northern Thailand) on the East. The people of the so called Shan states had extended onto the eastern side of the Salween river establishing Shan / Tai Yai settlements there – the towns of Khun Yuam and Mae Sariang were once referred to by Shan Names.

The border between the two territories was eventually decided at the beginning of the 19th century when an agreement was made between the Shan and Lan-Na chiefs that the river should be the dividing line. To seal the pact a buffalo was sacrificed in a ceremony at a site on the banks of the Salween river, and one of it’s horns divided in two; one half to be kept in Shan State, and the other to be kept in Chiang Mai, Lan-Na. According to the story it was decided that the agreement was to remain in place ‘until such time as the river ran dry, or the buffalo horn straightened’. This historical event is depicted with figurines in the Mae Sariang museum.

The rugged landscape of Chiang Mai’s remote western frontier always represented somewhat unfamiliar territory to the Thai lowlanders. Up until the 19th century the region had been a mysterious and inhospitable place on the margins of the kingdoms of Chiang Mai and Lan Na – the frontier with its tempestuous neighbour, Burma. Geographically speaking, i.e. being on the watershed of the Salween River that flows into Myanmar/Burma, the landscape is seemingly more a part of that country than of Thailand. Indeed, passage into Mae Hong Son’s central valleys has always been easier from the Burmese side.

If anything can be said to have been an abiding characteristic throughout Mae Hong Son’s history, it is perhaps it’s relative isolation from the outside world. For 35,000 years, since the late Stone Age, Mae Hong Son’s mountains and deep valleys have provided a safe haven for peaceful habitation. In prehistoric times the extensive cave systems in Pang Mapha district sheltered generations for thousands of years. Then, through subsequent centuries of conflict between competing empires of the South East Asian region, the mountains enclosing Mae Hong Son’s valleys acted as a protective barrier against significant outside interference.

For the generations of people who have lived there, Mae Hong Son’s relative isolation has had a fundamental and defining influence on their lives. Today, however, the valleys and mountains are seen not only have helped protect the indigenous people’s traditions, they have also been a barrier to community development and access to state services.

Ancient Civilizations

Thailand has a wonderfully rich an ancient history stretching back some 500,000 years. In 1999, homo-erectus skeletal remains were discovered in Lampang province, not far from Mae Hong Son. This was the first evidence of the nearest ancestor to homo-sapiens, our own species, found in South East Asia outside of China and Indonesia. The discovery of the ‘Lampang Man’ added a vital new piece to the incomplete puzzle of the history of humankind.

In Mae Hong Son province itself, further archaeological discoveries in the mid 1960’s by American anthropologist, Chester Gorman, revealed that early human civilizations inhabited the extensive cave systems in today’s Pang Ma Pha and Khun Yuam districts from around the late Stone Age (37,000 years ago) onwards.

Between 1998 and 2006 teams of archaeologists unearthed a large number of artifacts across 60 sites that helped to bring ancient civilizations to life. Sites included those used for habitation, ceremonial, burial, and manufacturing, and stunning rock paintings were also discovered.

Two of the sites – the Ban Rai (aka ‘Spirit Cave’) and Tham Lod rock shelters are typical of the sites in the region. The Ban Rai shelter, which dates back to between 10,000 and 600 BC was an Iron Age teak log coffin cemetery. Rock paintings found along the eastern flank of the site clearly indicate its ritual significance. The paintings depict birds and a large group of human figures, as well as other more abstract images. The large limestone cave was a sacred place and burial ground from the late Pleistocene period. A selection of the the excavated coffins are currently on display in the Chiang Mai national museum.

The Tham Lod rock shelter site, dating between 34,500 and 2,400 BC, is thought to have been permanently inhabited for up to 8,000 years from 10,000BC onwards. Excavations at that site revealed its various uses over centuries, including habitation, burial and manufacture. The presence of stone tools, lithic debris (i.e. remnants of stone tool production), animal bones and shellfish, helped to shed an amazingly detailed light on the lifestyle of those who lived there.

The Golden Road

The Golden Road refers to a group of overland trade routes linking Muslim communities in Yunnan, Southern China, to Upper and Lower Burma. By the mid 19th century the caravans of Yunnanese traders ranged over an area extending from the eastern frontiers of Tibet, through Assam, Burma, Thailand, Laos and Tongkin (Vietnam), to the southern Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Guizhuo and Guangxzi and Yunnan and they continued to dominate the caravan network well into the 20th century.

The Golden Road refers to a group of overland trade routes linking Muslim communities in Yunnan, Southern China, to Upper and Lower Burma. By the mid 19th century the caravans of Yunnanese traders ranged over an area extending from the eastern frontiers of Tibet, through Assam, Burma, Thailand, Laos and Tongkin (Vietnam), to the southern Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Guizhuo and Guangxzi and Yunnan and they continued to dominate the caravan network well into the 20th century.

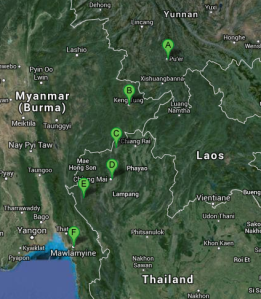

The routes that went through Thailand (left – point E is Mae Sariang) established trading posts with indigenous Shan and Karen communities along the Salween river. The settlements of Khun Yuam and Mae Sariang were the first major settlements in what was to become became Mae Hong Son province. Mae Sariang, a town known by a number of Shan names over the centuries, has a history stretching back some 500 years, due to it’s location on the frontier of Siam and Burma.

There seems to have been 3 routes that passed through Mae Sariang that are known collectively as the ‘northern route’. One route went from Chinese cities of Simao and Jinghong in Yunnan province, through to Kengtung in Shan state in eastern Burma, then to Fang, Chiang Mai, and Mae Sariang (Thailand), before crossing back into Burma again for its final leg on to the port of Moulmein. Another route reportedly ran from Simao to Mengla (Yunnan province), Chiang Khong, Chiang Rai, Phayao, Phrae, Chiang Mai, Mae Sariang (all northern Thailand) and on to Moulmein. A third route ran from Simao to Phongsali to Luang Phrabang (both in Laos), then on to Nan, Phrae, Tak (all Thailand) and on to Moulmein.

The merchants were known in Thailand as the ‘Chin Haw’, Muslim Chinese by extraction and closely related to the Panthay from Burma, a Muslim community there which had itself been established as a direct result of the Muslim trade routes. Both the Chin Haw and the Panthays are descendents of the the Chinese Muslims of Yunnan, called the Hui, formed a strong trading partnership and were noted for their mercantile prowess. Within Yunnan, the Muslim population excelled as merchants and soldiers, the two qualities, which made them ideally suited to the rigors of overland trade in the rugged, mountainous regions. Chinese Muslims, as a result of their faith were used to taking long and arduous pilgrimages, had established trade route with the Middle East by as early as the 14th century, and prospered greatly as a result thereafter.

In the nineteenth century, Haw caravans coming to Thailand from Yunnan increased in number, and their details were recorded by Western travelers and missionaries who were also moving around the region. Chin Haw mule trains, or caravans, were made up of up to 100 animals, accompanied by up to 15 mule drivers and armed guards who were trained in some sort of martial art. From China the mules were laden with things silk cloth, tea, metal utensils, iron in the rough, felts, finished articles of’ clothing, walnuts, opium, wax, preserved fruits and foods, and dried meat of’ several kinds. The Burmese goods taken back to Yunnan were raw cotton, raw and wrought silk, amber, jades and other precious stones, velvets, betel-nuts, tobacco, gold-leaf’, preserves, paps, dye woods,stick lac, ivory, and specialized foodstuffs such as slugs, edible birds’ nests, among other things

From 19th Century onwards the Chin Haw traders began to arrive into Thailand in greater numbers. The Muslim Chinese had been persecuted for a long time in China, first by the Han Dynasty, and then again by the Qing Dynasty, which ended up marching into Yunnan province in order to suppress an armed uprising that we now know as the ‘Panthy Rebellion’ (1856 – 1873). The second group settled as a direct result of the trade route, and over time set up communities at various locations along it. A third wave came following the Communist revolution in China in 1949. Many Muslims were forced to flee into neighbouring territories, especially Burma, and in time they established communities along the Thai-Burma border that exist to this day. Two of the more well-known Chinese communities that exist today, now popular tourist destinations, are located at Baan Rak Thai (Mae Aw) in Mae Hong Son, and Mae Salong (aka Santikhiri) in Chiang Rai province.

Today there is a substantial Yunnanese-Muslim population of approximately 50,000 in Chiang Mai province alone. Several mosques have been built in Thailand’s northern provinces by the Chin Haw traders – the biggest and most famous of which is Baan Ho Mosque in the city of Chiang Mai. Similar Muslim communities exist in a line between China, Laos, Thailand and Burma, and today these people continue to represent both Chinese and Islamic cultures in this northern part of South East Asia.

1831 – 1933

Mae Hong Son as a place-name first enters Thailand’s historical record in the early 1830’s when a royal party, led by Lord Kaew of Ma, a relative of the King of Chiang Mai, was sent on a mission to explore the remote western frontier. The primary purpose of the mission was to round up and train elephants – the animals from the mountains and valleys were known to be especially strong and they were to be trained and sent out across the kingdom for work and possibly even warfare. Lord Ma’s mission was a great success and he established a new settlement next to a lake by joining different Shan villages together. This became the town of Mae Hong Son.

Considering the shifting balance of power in Burma at the time, a geopolitical motivation behind the mission may have also been a factor. The British occupied the Burmese port of Moulmein in 1826, and perhaps fearing a similar fate the Chiang Mai ruling elite decided to shore-up the borders and project greater influence over its permeable Western frontier (Mae Hong Son shares a long border with Burma along the Salawin River. The river flows into Burma and Moulmein lies at it’s delta. Thailand didn’t really draw it’s own northern borders, they were more ‘imposed’ on them as a result of colonialist occupation in neighbouring countries. The British drew the border of Burma, and the French drew the border of Laos – the north of Thailand got the space in between!)

Mae Hong Son quickly grows in size and by 1874 the town is deemed big enough to become a city (meaung), with it’s own leader and able to administrate its own affairs. The leader of Chiang Mai elects a local charismatic Shan, called Chan Ka Le, to be the headman and with the change in status his name becomes the more auspicious Phaya Singanat Racha (his statue stands at the foot of the hill on which stands Mae Hong Son’s famous landmark, Wat Phra That Doi Kong Mu).

In 1890 Mae Hong Son is visited by a delegation from Bangkok and it is decided to place the province under Chiang Mai’s jurisdiction. The administrative centre moves from Khun Yuam to Mae Sariang in 1903, and then to Mae Hong Son in 1910. In 1933 Thailand’s new constitution comes into force and governance of Mae Hong Son as an independent territory ceases and is reinstated as a province under the new constitutional government of Thailand that exists to this day.

World War II

The Road through the Mountains

The road through the mountains from Chiang Mai (starting at Mae Malai) to Khun Yuam, via Pai (today’s Rte’s 1095 and 108), was originally constructed by the Japanese military during World War two. The road became known as the ‘Death Road’ due to the number of people who died during its construction.

Japan joined the war against the western Allies and created an army base in Chiang Mai in order to plan and launch an attack on British Burma. The Burmese town of Taungoo was apparently seen as a vital transport and logistics hub and the Japanese planned to take it over directly from Mae Hong Son.

The Japanese army forced villagers to work on the route from Chiang Mai to Mae Hong Son and the other way from Mae Hong Son to Chiang Mai simultaneously. The road eventually meets in the area of Pai. British aerial reconnaissance records display an entry reporting the sighting of Japanese forces constructing a road from Chiang Mai towards Pai and from Mae Hong Son to Pai but downplay its importance.

The river just east of the town of Pai was a tricky obstacle and the Japanese oversaw the construction of a wooden road bridge there using elephants which dragged 30 inch wide trees from the surrounding forest. Later on, the retreating Japanese soldiers burnt down the bridge behind them on their way back to Chiang Mai. For the local community this was a big loss. The people had grown to value the crossing a great deal and once it had been destroyed they had to fashion wooden boats out of tree trunks to in order to cross the river. The community eventually came together to rebuild the wooden bridge and this lasted until 1973, when there was a huge flood that caused damage to the surrounding paddy fields and farms destroying the bridge in its wake.

The Pai district office asked the neighbouring Chiang Mai province for permission to have the Nawarat Steel Bridge to re-open the crossing and in 1975 that bridge was transported to Pai and reassembled reconnect the two banks once again. The Nawarat bridge was itself replaced by a modern concrete bridge in order to take a rising number of heavy vehicles. The Nawarat steel bridge remains right next to it although it is only used by cyclists and photographers. The old metal bridge from Chiang Mai is often mistaken for the original WW2 bridge, but this is not a fully accurate description.

(This basic website contains a large amount of specialist WW2 military information, including reconnaissance data on microfilm along with grainy aerial shots of Mae Hong Son province taken during the war.)

Retreat to Khun Yuam

The Japanese were defeated in 1945 and 100,000 troops retreated unaided through the Burmese jungles into Thailand, along what became known as ‘the skeleton road’. 20,000 died before even reaching Thailand, and those who did manage to cross the border mostly descended on the town of Khun Yuam in Mae Hong Son province. A temporary military field hospital was set up at a Shan temple, Wat Muay Tor, to treat the wounded. 30 Japanese army medical officers were stationed there and would quickly survey the new arrivals, marking an ‘X’ on the souls of those who were thought not to be worth saving. Upwards of 7,000 died in Khun Yuam itself – their ashes kept along one of the temple walls in urns.

With the soldiers came death and disease, which also infected and killed many local Thai residents too. The departing troops left a large quantity of military equipment behind them but this was left to decay through a mixture of fear and respect for the dead. In 1995 the head of police in Khun Yuam began collecting the items himself – everything from water canisters, to rifles, to the rusting cabs of troop carriers – and ended up establishing a very good museum at the site of the Khun Yuam Cultural Centre to house them in. The museum recently underwent an expensive refit and it is open for the public to view today.

WW2 Gallery (obtained from the Khun Yuam WW2 museum).

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand

- WW2 Japanese Soldiers in Thailand